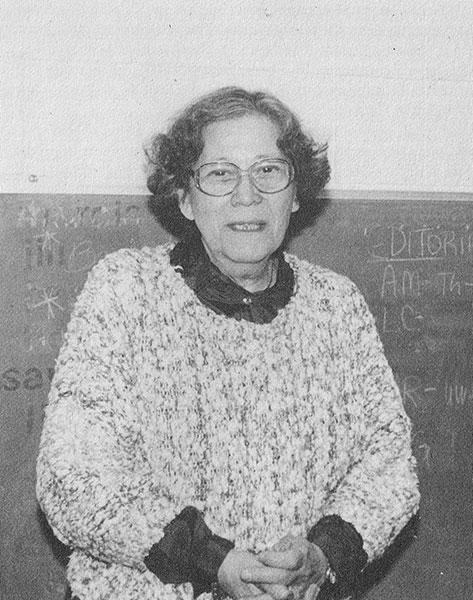

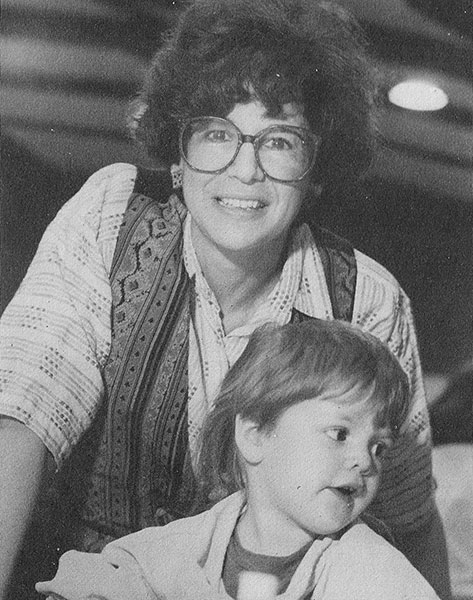

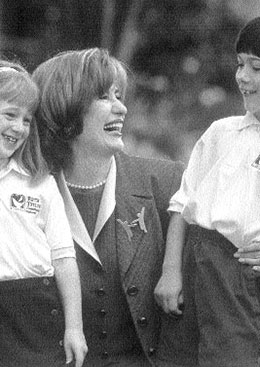

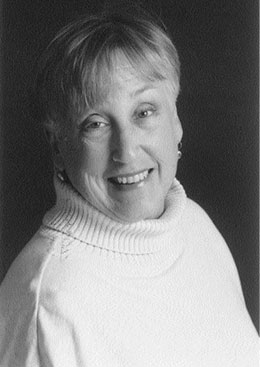

1996 Covenant Award Recipient

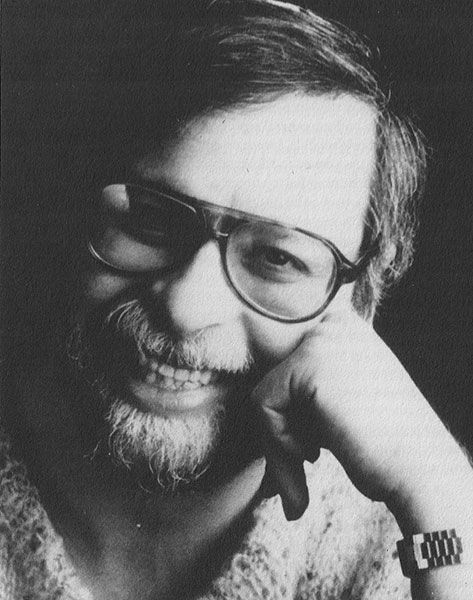

Debbie Friedman z”l

Debbie Friedman learned the wisdom and wonder of Judaism around the farmhouse kitchen of her grandparents, Eva and Bill Chernoff in Utica, New York. When she was five, her father accepted work in St. Paul, Minnesota, and the Friedmans moved 1,000 miles away. As an elementary and Hebrew school student, young Debbie struggled with reading comprehension. In time, frustration led to the conviction that she was inferior. “I really thought I was running on a deficit of intelligence,” she says, a refrain often heard from learning-disabled adults who went undiagnosed as children. Throughout her life, what she learned best, she always learned by ear. It was not until she reached her thirties that she understood that a tracking problem in her brain prevents her from arranging letters and musical notes in proper sequence. A computer synthesizer now allows her to compose on a keyboard, translating her melodies into correct time, signature, key, and form.

In high school, her gift for melody merged with her unshakable connection to an ancestral past. Ms. Friedman’s acoustic melodies are rooted in the era of Bob Dylan and Joan Baez. At age 17, she acquired her first twelve-string guitar and, without the benefit of formal musical training, began writing Jewish music. Upon her return from a post-graduation stint in Israel, she gained notice in the United States as a song leader at various Reform congregations and summer camps. Once, on a bus bound for New York, a melody came into her head. She married it to the “V’ahavta” prayer – ‘And thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart’ – and taught it to students at a conclave. “All of a sudden they stood up, grabbed each other’s arms, and joined in this prayer,” recalls Ms. Friedman. “I realized something powerful was happening.”

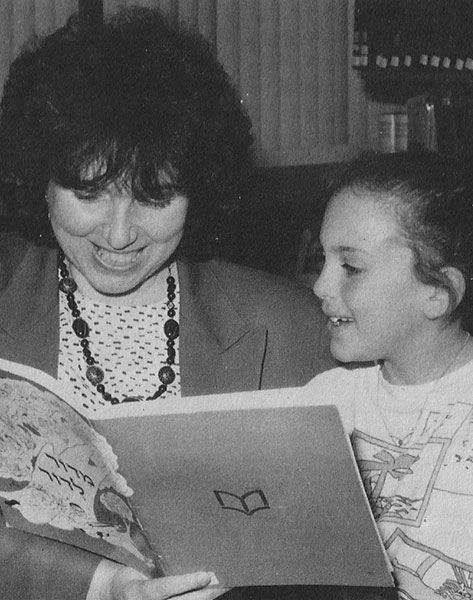

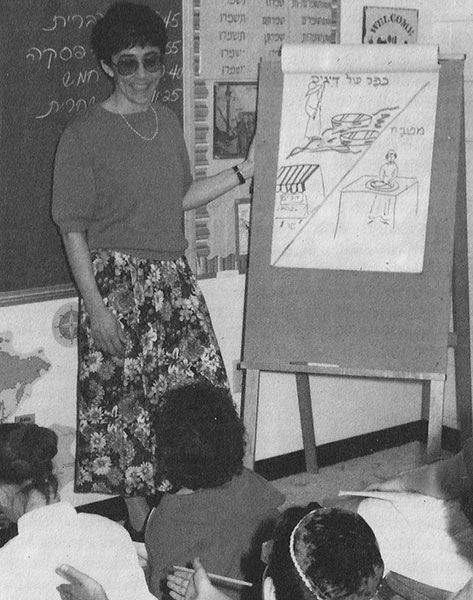

Through teaching and cantorial positions in Houston, Chicago, New Jersey, Palm Springs, San Diego, and Los Angeles, Ms. Friedman spent the 1970s and 1980s writing cantatas, choral works, and dozens of funny and tuneful Jewish songs for children and adults. For someone who is described as having invented a unique style of American Jewish music, Debbie Friedman is still always connected, with great humility, to her source: “I feel that what comes through me is what I was put here to do. It’s a gift, and it doesn’t belong to me.”

Debbie Friedman's Statement of Motivation and Purpose:

“My father was a kosher butcher in Utica, my mother a housewife. My bubby and zaydy lived upstairs. Every yom tov was celebrated with the whole family. My father would bring home ‘chickie eggs’ from the butcher shop. On Pesach, bubby and zaydy would pull out the dishes and, particularly, the red glasses that had places for our thumbs to rest. Every Shabbat that bubby and zaydy were home, bubby put a paper napkin on her head and lit the Shabbat candles, first reciting the b’racha and then the special prayer for everyone who was in ‘Gan Eden.’

I begged my parents to send me to Hebrew school. I was told that I was too young. I begged to go to day school, but the only one was far away. Finally, when I was in second grade, my parents agreed to let me go to Hebrew school at the Conservative synagogue even though we were members of a Reform synagogue. I graduated from Hebrew school and became active in the Temple youth group in our region. One day I picked up a guitar because I wanted to play just like a friend of mine. I never put it down.

One night while I was at services, I realized that I was sitting passively. The choir sang, the rabbi talked, and no one participated. I knew that if I felt alone and isolated from the tradition that was so important to my life, and I was involved, then what of those who were not involved? What must they have felt? I have never forgotten that moment. That was the inspiration for me to write. I still write for all of those people, students, teachers, and parents who don’t know how to connect to the tradition as theirs, to the liturgy as theirs, to the idea of spirituality as theirs, to the healing process as theirs.

My bubby‘s legacy to me was not only the paper napkin on her head, the b’racha for the living, and the blessings for those not with us. Her napkin on her head became my napkin on my head, my music, which is your music, which continues to come through me in order to reach our origins. Seeing the impact of my music on people helps me continue to create. It is my hope to continue to help others find their true gifts – music, education, social work, administration, parenting – through our sacred texts so that people are able to discover who they are, so they may go forth and be a blessing.”

From Her Letters of Support:

“The Tikkun Zohar, 13C, states that there are palaces that are open only to music. Through her music Debbie has opened palaces of Judaism for thousands of Jews. Perhaps more than any other person in all of North America, her music has taught the words, the content, and most important, the love of Judaism. Beginning with her work in Reform movement summer camps, she has influenced an entire generation of song leaders, and through them thousands of Jews. Her music has become commonplace in most synagogue services, in youth group movement events, at summer camps, in schools, and in synagogues throughout the world.”

Rabbi Stuart Kelman

“Debbie is the inheritor of a great legacy. I’ve sung with her and watched her perform many times, sometimes in the wee hours at spontaneous gatherings during Jewish education conferences. Hers is the music of jubilation and confirmation. It is a call to community and commonality.”

Peter Yarrow, of Peter, Paul, and Mary

“She says her road to Carnegie Hall is a road back to bubby and zaydy, the primary religious influences in her life. Where’s God? Bubby didn’t know from intellectual theology and archaeological prooftexts. All she knew was that on Friday night she put a paper napkin on her head and God was in the farmhouse as she whispered a blessing over the candles. Everything seemed holy. There were angels in the farmhouse, according to the bedtime Shema, guarding her while she slept. Years later, long after the Reform and Conservative prayerbooks eliminated any mention of angels from the bedtime prayer, the little girl within the mature composer wrote music to match the memory of Angels Michael, Gabriel, Uriel, and Raphael, in her bedroom in the farmhouse in the dark. Her grandparents did not sing zemirot at the Shabbat table. Her music was farm fresh, American, more like the Weavers or Leadbelly. Yet it is Jewish, insofar as the songs are infused with the idea of God and Biblical verse. She wrote new music to the famous first line of Shema, and turned Kaddish into a love song, which lyrically it always was. Debbie participated in the preparation of bubby‘s body for burial, pouring the water, thinking of the old times in Utica when bubby would dry her after a bath. Where’s God? In a farmhouse lullaby for a five-year-old girl on her last night before leaving for lonely Minnesota, in the piano and guitar, in the pouring of water, in healing. Where’s Debbie? In Carnegie Hall, with God and bubby.”

Jonathan Mark, The New York Jewish Week