ARTICLE New Jewish “Texts”

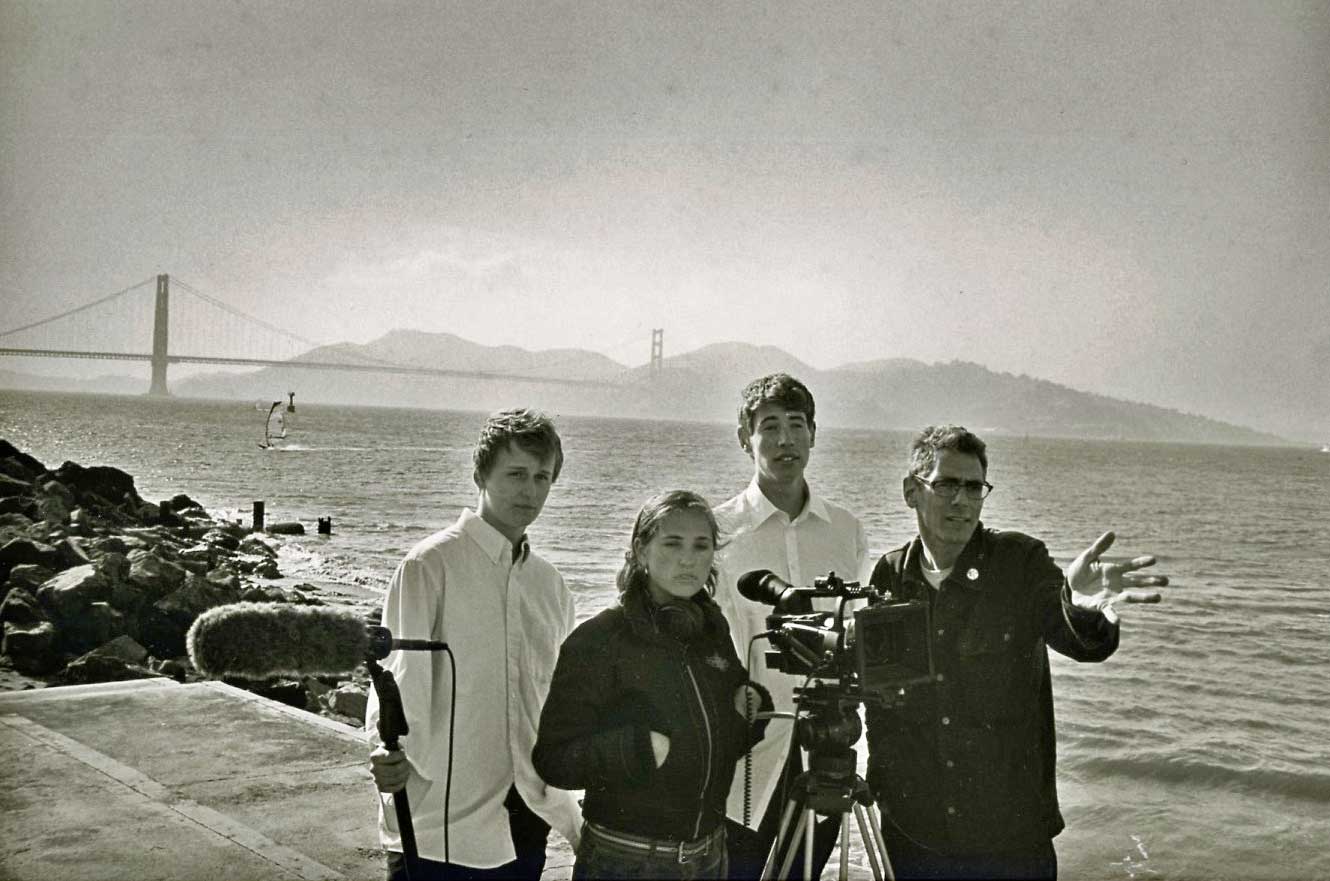

I think [creating new Jewish texts] is a really good description of what we’re trying to do. These days we’re increasingly creating products that are intended to be shared on the web. We’ve felt and continue to feel that this medium, and virtual communication as a whole, is being under-tapped for its possibilities for making art.

And that’s one of the main things we’ve tried to accomplish in working with young people—try and figure out how they are using online tools to communicate and try and harness those tools to create coherent artistic expressions in a form that feels authentic and native to the maker. This is supported by all kinds of data showing that most people who view and consume media on the internet also create, and that’s most true for this age group of 18-29. So it has been really exciting to see what kinds of forms people in this age group can come up with. Obviously, Jews are not unique to this phenomenon. However, one of the things that we’ve been interested in doing lately is collaborating with scholars to ask, “What can be Jewish about the way these tools are used?”.

One scholar shared a theory with me that the printing press created all of these revolutions in Jewish thought and the way that Jews looked at textual analysis. And what’s happening now is analogous in some ways. The technology is forcing people to look at questions of ownership and questions of cultural transmission; to think of ways that we look at texts and share texts and learn from texts. And texts can be brought into multimedia through video and photo stills and images. Increasingly, we’ve got these phenomenal archival resources available to us to organize and remix and communicate with. And that’s very exciting in the Jewish world, and also underutilized. There’s been a lot of expenditure of money and energy in digitizing the Jewish record from genealogy to literature to photos, and increasingly film. Now, we’re at this moment when we can unlock all of that and remix it and make it relevant.

On the NJFP.org website, we have a project called “Half-Remembered Stories.” One is a “choose your own adventure” story, like what we read as kids. The maker of the project researched her own family story, so visitors navigate through history as her great-grandmother. But only one thread is what actually happened, and there’s a video at the end that shows the factual history. The other threads are ones that the filmmaker researched about decisions Jews were faced with during the 20th century and how they responded to those decisions. So it’s an amazing combination of deep historical research and personal expression. And the third benefit is that it’s very sharable: it’s a game you can play, so this is an example of documentary gaming, which is a completely new form.

Instead of thinking about filmmaking as one person communicating with many people, it really becomes a joint community endeavor. You’re constantly thinking about questions of collaboration and questions of education, such as, “How do I research and what’s my responsibility as a researcher in terms of factual accuracy?” You think about all of these questions of individual roles vs. community responsibility and community sharing. Covenant has been uniquely forward thinking in embracing art as a way to explore these kinds of questions, and I’m very grateful for that.

By Sam Ball, for The Covenant Foundation