ARTICLE Moving Traditions’ New National B’nai Mitzvah Program, for Families

If one were to survey Jewish parents about what they think the most pivotal moment is in their child’s Jewish journey, chances are a majority would answer the B’nai Mitzvah. But whereas the ritual is meant to symbolize a moment when a young person stands at the dawn of a rich Jewish life to come, more often than not these days, the B’nai Mitzvah represents the opposite: an ending of sorts.

Often, with the B’nai Mitzvah, comes a slowing down of a young person’s time in synagogue, less frequent attendance in religious school, and for many families, the culmination of a journey that was just starting to rev up.

“As we conducted research with groups of Jewish teenagers, we heard a lot about how proud and how good they felt about having a B’nai Mitzvah, but we were also painfully aware of how much they saw the moment as a graduation from Jewish life,” shared Deborah Meyer, Founder and CEO of Moving Traditions, the nonprofit organization that has recently launched a national program for B’nai Mitzvah students and their families.

“It’s also a difficult moment,” Meyer continued, “as parents are figuring out how to raise a teen, and children are transitioning into their teenage years. The Jewish community should be helping families navigate this moment, which is filled with issues that are challenging, but also very sweet and meaningful.”

At the start of 2019, with a field-tested curriculum designed by rabbis, social workers, and psychologists, Moving Traditions began doing just that, as the organization presented a program to synagogues that uses their signature model of informal education to address the “social realities” of sixth and seventh graders and their parents.

“Every child develops differently, but there are patterns that sociologists and psychologists have urged educators and parents to pay attention to,” said Rabbi Daniel Brenner, Chief of Education at Moving Traditions. “The period that begins around ages 13-15 is a time where adolescents look more toward their peers for social cues than they do toward any other adult, including their parents,” he said.

Brenner added how essential it is for adolescents to have mentors during the 8th-10th grade years, because those are the times that can present the most opportunity for risk and dangerous behavior amongst teens. They are tuning out adult voices as much as they can—a developmentally appropriate move—and they are under so much pressure both socially and academically.

“But what we also know,” Brenner said, “is that 6th grade, where the vast majority of students are 12 years old, is a moment when kids tend to still be ‘in conversation’ with their parents, and so it offers a window of opportunity to establish good communication skills and support practices—both for children as well as for parents.”

Brenner explained that this age is critical, and may be one of the last stages where it’s possible to have parents and children in the same room conversing with relative ease, free from some of the tensions that develop as kids enter more deeply into the teen years.

“We also know that intimacy between parent and child starts to diminish even in elementary school,” Brenner said, “and that process continues through the 6th grade. Parents are reading less to their kids before bed, parents aren’t necessarily comforting their children after a playground fall, for example, or administering medicine when a child gets a cold. Understandably, parents begin to urge their children to do these things for themselves. But as a parent withdraws from the physical needs and care of their child, some kids who felt coddled might rejoice in their newfound independence, but others begin to grieve, missing the loving touch of their parents.”

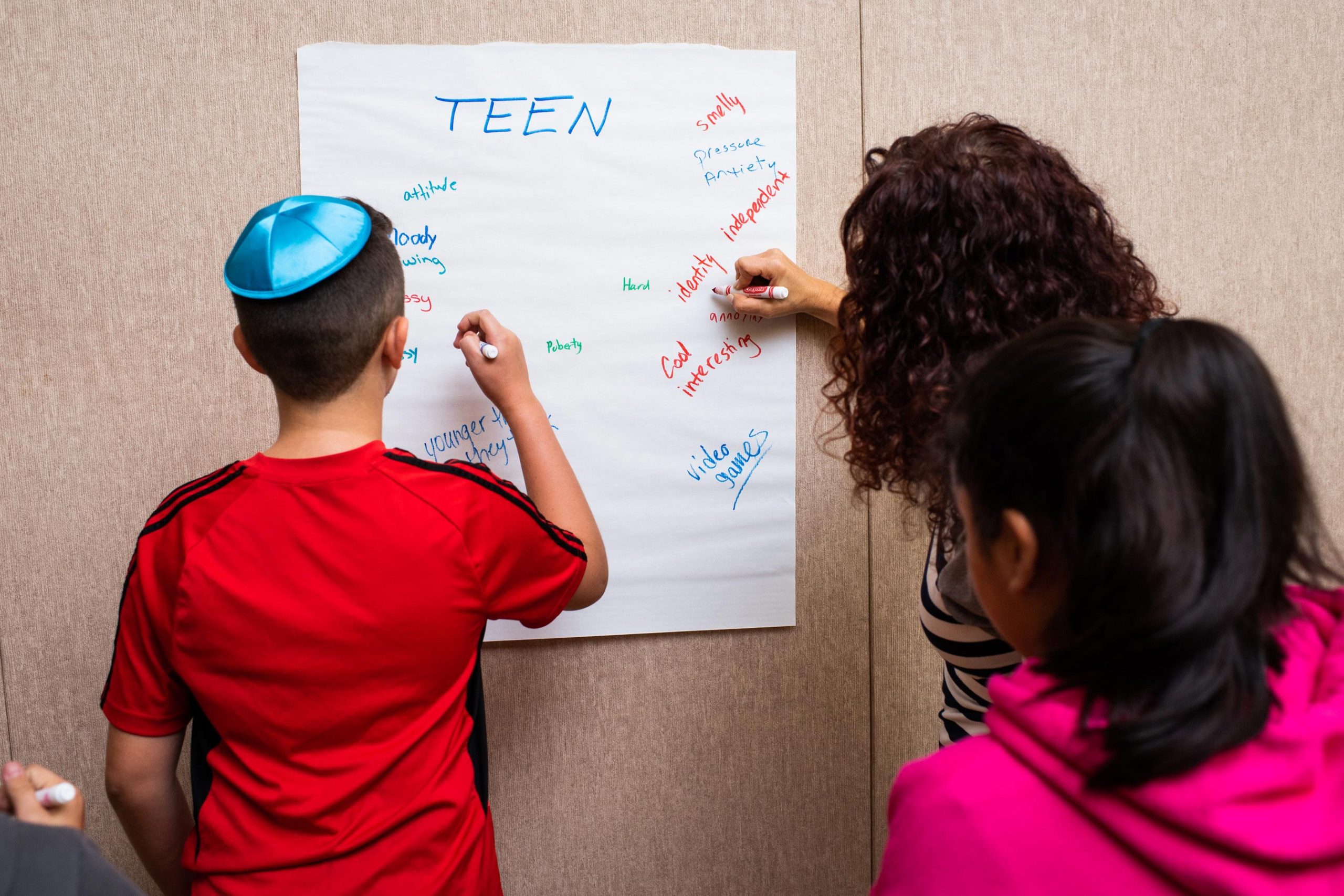

Brenner and Meyer explained that in this transitional moment, just before the B’nai Mitzvah, focusing on ‘big issues’ is most profound. For that reason, the Moving Traditions B’nai Mitzvah curriculum centers around questions like: What does it mean to become a teen? How do I navigate being the center of attention? What are the obligations of hosts and guests? How is parenting a teen different then parenting a child? (Many of these questions are also explored on the original Moving Traditions podcast, @13.)

It may seem obvious that these are questions that we should be asking ourselves and our kids as we prepare for such a momentous occasion, and yet, research has shown that at American synagogues today, more often than not the conversation surrounding B’nai Mitzvah is focused largely on logistics—the date, the caterer, the venue—and not necessarily on the substantive and meaningful aspects of the event.

Meyer and Brenner understand this phenomenon as the result of many different factors at work—so many of which are part of a larger conversation about how parenting has changed from 25 or 30 years ago. They cite factors like the professionalization of childhood, the realities of households with two working parents who in so many cases are trying to make ends meet, and daily schedules that are crushing to both kids and adults alike.

But here’s the good news: In their research, Meyer, Brenner and their colleagues at Moving Traditions have also found that families truly want the Jewish community to step in and create experiences that address their needs.

“We are finding that there is definitely an appetite for family education,” Brenner said, “but it has to be designed with parents and preteens in mind for it to actually work.”

When looking at the data that they culled from the first year of the program, Meyer, Brenner and their colleagues found that of the over 900 families surveyed about their experience with the new B’nai Mitzvah curriculum, the majority of parents responded that what they enjoy most about it is just being together with their children. The second aspect most valued by parents surveyed? Being with other parents.

“This tells us a lot about the potential,” Brenner reflected. “If you structure a conversation well, and make sure there’s a well-trained facilitator who can help that conversation hit the right message with the right tone, parents and kids will notice, and be far more inclined to want to continue having those talks in a community setting” he said.

And their theory is bearing out in the numbers, too. In fact, 73% of participating synagogues who ran the program in its first year hosted two or more family sessions in addition to the student-centered learning, and the vast majority did even more, averaging between 2-4 family sessions during the year. Brenner added that through this experience, parents and kids alike begin to see that the Jewish community is a place that can help teens thrive, talk about friendship, and examine unreal expectations.

“Our teen groups [Rosh Hodesh and Shevet] are focused on creating peer community and learning how to be part of helping create community,” Meyer said, “so that teens can do that for themselves moving forward. And the B’nai Mitzvah program is yet another opportunity for creating community—for parents. We are giving parents the chance to see that rather than thinking of B’nai Mitzvah as something that they do for their kids, or to please the grandparents, it’s an event that reinforces and strengthens Jewish community.”

Meyer explained that in creating the B’nai Mitzvah program, Moving Traditions strove to understand which key issues were at work at this moment in history, and what the real-life developmental and historical issues are that come up at this time in the life cycle. Then, there’s the question of how Jewish teachings apply to those issues. In response, Moving Traditions staff created resources and tested them. And central to this work and everything Moving Traditions does, is ensuring that participants from different socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds will find something meaningful and useful and necessary in the sessions they attend.

Perhaps most critical to the program’s success, according to Meyer, is the fact that Moving Traditions prepares clergy and Jewish educators to explore through Jewish teachings the social-emotional and developmental issues that arise in families at this transition from child to teen. (This training is actually the focus of the Covenant Foundation’s funding to Moving Traditions.) The Carol Lowenstein Moving Traditions B’nai Mitzvah Training Institute has been found to be truly valuable by clergy and educators, even those with many years of experience in B’nai Mitzvah preparation, because it connects “real life” issues in adolescence and parenting with Judaism.

“What Judaism provides for those of us that find meaning in it, are moments where we can stop and think about our lives and be intentional about how we’re living,” Meyer said.

“The B’nai Mitzvah is a liminal moment in Jewish life,” she added. “Children are becoming teens, and in some cases, they are preparing to leave the Jewish fold. How do we create experiences that will serve them and their families and institutions?”

Meyer answered her own question. “First,” she said, “we start with reframing the ritual as one that’s most centrally about becoming a teenager, and helping parents think about the social and emotional realities of that,” she continued. “And that’s really key, today especially, as our society becomes more and more atomized, and we all struggle to find meaning.”

“Through this experience, of talking and learning together, we’re hoping to provide families with an experience that is incredibly relevant to them.”

By Adina Kay-Gross, for The Covenant Foundation

More to Consider

- Moving Traditions’ New B’nai Mitzvah Traditions (Jewish Journal)

- New Program Aims to Get B’nai Mitzvah Teens to Open Up (Jewish Journal)

- Meaning Making for Teens: An Interview with Deborah Meyer (Sight Line, Volume 5)

- How a New Model of Family Education Places the Parent-Child Relationship at the Center of the B’nai Mitzvah Experience (eJewish Philanthropy, March 18, 2019)

- Thinking Differently About B’nai Mitzvah (eJewish Philanthropy, October 30, 2018)

- Baboons, Bonobos, Bar Mitzvah Boys (Rabbi Daniel Brenner's ELI Talk)

All of Our Voices: Moving Traditions’ Kol Koleinu Teen Feminist Fellowship

997