ARTICLE Build a School Inlaid with Love: An Interview with Dr. Rebecca Schorsch

Dr. Rebecca Schorsch loves working with teenagers. And while some educators might find that particular demographic challenging, or overwhelming (so many hormones!) Schorsch finds that the vulnerability teenagers are willing to share allows for a sense of openness in the classroom that’s invaluable to the project of growing a love of Judaism and a love of one another.

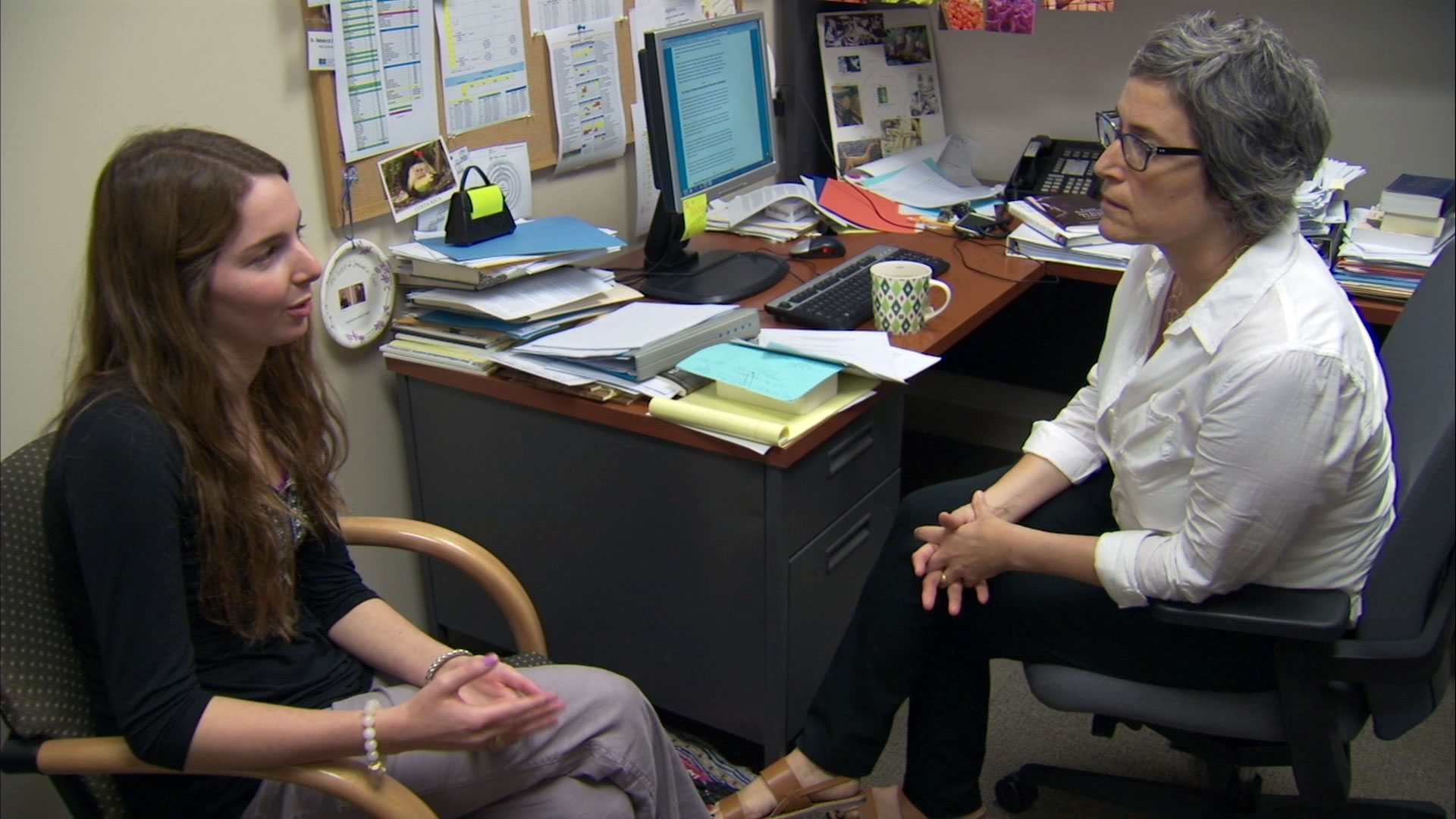

“Teenagers are naturally seeking their own sense of who they are,” Schorsch said from her office at the Rochelle Zell Jewish High School in the suburbs of Chicago where she serves as Director of Jewish Studies. “They’re thinking about authenticity and integrity, and while their process of individuation can be scary for adults to witness, it’s such a gift for educators who get to shepherd them through these meaningful moments and help them decide who they want to be in the world.”

A 2014 Covenant Award recipient, Schorsch has been working as a Jewish educator for 28 years, dating back to her days as a counselor at Camp Ramah in Wisconsin. In fact, she credits some of the introspection that she did back then as a young 20-something with her approach to teaching, today.

“I had this moment at camp as a young adult counselor,” she said, “where I really grappled with the question of how we teach ‘Jewish obligation,’ to our campers, and I remember thinking to myself that if we could find a way to make obligation compelling to kids, in a language that would work, in a liberal and open way, that would be helpful to them. Then, we could send them off knowing that they ‘got it,’ and their commitment would be solidified.”

But it was later, while in graduate school, when Schorsch began to study the teachings of Martin Buber, that the roots of what would become her central pedagogy really took root. Buber’s I-Thou philosophy— that all of actual life is relationship and in relationship, or the I-You, is also a relationship with God”—reflects how Schorsch understands what her central task is with her students: to bring love into our Jewish classrooms, and to nurture her students’ love of Judaism, she fosters relationships first.

“I’m not really grappling with obligation anymore,” she said. “Rather, I am thinking about love, and I think that a sense of duty and responsibility to living a Jewish life must emanate from a place of love, between teacher and student, student to student, student to text, and so many other forms. That’s what the classroom needs to be about.”

But love is a topic that seems bound to make teens giggle at best, or, clam up and reject any attempts to talk about it, at worst. It’s hard enough for adults to talk to one another with a language of love and kindness and empathy without feeling that they’re falling into dangerous sentimental territory, or that they’ll be overexposed or misunderstood. At a time when we’re more isolated from one another than ever before, thanks to technology and political divides and wide socioeconomic chasms, the challenge of bringing love back to the learning that’s happening in our classrooms seems almost insurmountable.

But Schorsch has specific methods. It begins with her mindset: she feels respect and admiration for her students and wants them to know that, to feel it. She knows they’ve made a choice, either actively or as part of their family’s values, to attend Jewish day school. She appreciates that choice and feels it’s imperative to honor them as human beings, as people who are very capable.

Schorsch is also very mindful of what her classroom feels like. “I'm obsessed with body language, and the possibilities inherent in face to face interactions,” she said. “So anything that’s an obstacle to that, I try and eliminate.”

That means there are no computers or screens in Schorsch’s class. Students are working with good old-fashioned books and pen and paper. They are looking at one another, facing one another, and making eye contact. “As a teacher, you must ask open-ended questions and you must be deeply interested in their answers,” Schorsch said. “Part of that process is showing your students your genuine interest; my students can see me nodding and I can see them and their reactions, and those elements are essential as we begin our work together,” she said.

Schorsch is not afraid of her students being bored, either. “Without their screens, they may be bored, they may doodle, they may stare at the ceiling, they may even put their head down for moment, but that’s OK,” she said. “They’ll come back.” Schorsch believes, as many do, that boredom is a value that’s all but lost on kids today. It’s not a bad thing to have the mind wander aimlessly and in fact, can be quite useful for discovery and self-knowledge.

“I think they appreciate the break from their phones,” she adds. “When they're out in the halls, their phones come out. But at least for a short while each day—whether it’s the 40 minutes they spend in t’fillah in the morning or in my classroom, it’s a chance to take a break.”

Schorsch’s students also spend time journaling and reflecting before they enter into a study of any text, because, as she put it, “this process helps us figure out where they are, and helps them see themselves and their own life experiences in the text.”

For example, in her 12th grade Modern Jewish Thought class, the first long, book-length text Schorsch’s students read is Rav Joseph Soloveitchik’s essay The Lonely Man of Faith. “I was honestly surprised,” she said, “by the extent to which that essay really resonates with teenagers. We know that technology has made us all more isolated from one another, but my students understood that Soloveitchik is talking about how to be human is to experience loneliness and as teenagers, this idea resonates deeply with them.”

“I think one of things adults do is try and shield them from feeling lonely or isolated, or say ‘don’t worry about it,’” she continued. “But in my class, I want us to look at the feelings, and be open about them. Loneliness and other difficult feelings aren’t meant to be swept under the rug, but rather, we need to take these feelings seriously, and name what we are feeling and see these feelings as an opening to connection, as necessary to connection, as does Soloveitchik, as the self---understanding, enabling, turning toward one another and God.”

“In my class, I am trying to foster an opening, not a closing,” she continued. “I don’t want my students to be afraid of sharing big feelings; these are the conversations I want to have with them.”

Any high school teacher knows that those four years are a time of intense pressure for students. And while the world that Schorsch’s students are living in—the world we are all living in, actually, commodifies everything, she finds it essential to help her students see that the entirety of their being isn’t determined by their GPA or the college they’re accepted to. Rather, she hopes to give them an alternative way to imagine themselves.

“All that commodification is so anxiety inducing,” she said. “You cannot possibly think about yourself in a deep way if you’re just thinking about your resume. In fact, the least of my concerns is whether my students are going to become doctors or lawyers. Rather, I want to know how they’re going to respond when bad things happen. Do they close off and disconnect? Do they become angry? Do they cry out against injustice?”

When Schorsch’s students read the Book of Job, she tries to help them make connections to their own lives and see how the text can inform decisions we make about who we want to be in the world, to acknowledge that bad things happen in the world, and to figure out how we respond to those bad things. She finds, too, that a teacher’s willingness to be open is critical.

“I think a teacher’s openness is derived from her sense of aliveness, and a sharing of a teacher’s own love. Is the teacher present and excited? That’s how students in the room will feel love; if they can sense their teacher’s own love for text, for education, for potential.”

Schorsch recognizes that the time her students spend in high school may be stressful but that it’s also a time of substantial growth. She sees her task then as helping her students fall in love with Judaism, Jewish text, Jewish culture—and Jewish life—because all of that is part of helping them develop who they will be as Jewish people in the world, and how they will live in the world with meaning. She sees her students’ choices to keep Shabbat, kashrut and a life of chesed about feeling not only deeply connected to their Jewish past and Jewish communities--as Soloveitchik writes, not as a hitchhiker unaware of her starting place and unsure where she is getting off--but rather as people who are deeply rooted and securely able to interact in the world.

Schorsch is reminded of a verse from Shir HaShirim (3:10) that describes King Solomon’s temple as,

עַמּוּדָיו֙ עָ֣שָׂה כֶ֔סֶף רְפִידָת֣וֹ זָהָ֔ב מֶרְכָּב֖וֹ אַרְגָּמָ֑ן תּוֹכוֹ֙ רָצ֣וּף אַהֲבָ֔ה מִבְּנ֖וֹת יְרוּשָׁלִָֽם׃

or, “inlaid with love.” The verse inspires how she thinks of the school environment she’s hoping to create for her students. “I always wonder, what does that mean, to build a structure that’s ‘inlaid with love?’ What does a school look like if it’s ‘inlaid with love?’”

Schorsch answers her own question. “A school inlaid with love is created through meaningful conversation, face to face encounter, by looking at each other, by careful reading and by not mishearing one another. We can create a love by not imposing our own language onto a text, but rather, by being aware and thoughtful.”

“I set the bar really high,” she added. “But teenagers are exciting to me. Their potential is so enormous. I want to cultivate patience, and have them sit around a table for a long time and just listen to each other. And ultimately I want to challenge them to think. Here is where they can truly begin to become the people they’re meant to be.”

By Adina Kay-Gross, for The Covenant Foundation. Photo by Zion Ozeri.

More to Consider:

- On Being Uncomfortable, By Dr. Rebecca Schorsch, Facebook, August 2018

- Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age, by Sherry Turkle

- Stop Googling, Lets Talk (Sherry Turkle, The New York Times, Sept 26, 2015)

- Dr. Rebecca Schorsch, Covenant Award Acceptance Speech Film (November 2014)

- Dr. Rebecca Schorsch, Covenant Awards Film 2014

- On Jewish Learning (Franz Rosenzweig, edited by N.N. Glatzer)

- I and Thou (Martin Buber)